Aliados Square, 1943. Early works: Nadir Afonso already displays a preference for urban themes, which he will extensively develop in the Cities series.

As a theorist of his own geometry-based aesthetics, published in several books, Nadir Afonso defends that art is purely objective and ruled by laws that treat art not as an act of imagination but of observation, perception, and form manipulation.

Nadir Afonso achieved international recognition early on in his career and currently holds many of his works in museums. His most famous works are the Cities series, which depict places all around the world. As of 2007 he is still actively painting.

Évora Surrealista, 1945. Surreal period, denoting a drift to abstractionism at age 25.

Nadir Afonso Rodrigues was born in the rural, remote town of Chaves, Portugal, on December 4, 1920. His parents were Palmira Rodrigues Afonso and poet Artur Maria Afonso. His very unusual first name was suggested by a gypsy to his father on his way to the Civil Registry, where he was due to be registered as Orlando.

By the age of four, he made his first "painting" on a wall at home: a perfect red circle, which anticipated his life as under the signs of rhythm and geometric precision. His teen years were dedicated to painting, earning him his first national prize at age 17. It was only natural that he was sent to the bigger city of Porto to enroll in the School of Fine Arts for the art (painting) degree. However, at the registration desk, he took the advice of the clerk, who told him that his high school diploma allowed him to enroll in Architecture, which was then a more promising career. As he later admitted, he made a mistake by listening to that man.

Composition, 1946. Iris period: first purely abstract works.

Still, Nadir Afonso took on the challenge and completed the graduation in Architecture, but he had to flunk the third year because some of his professors could not accept Nadir Afonso's artistic style. Settled in Porto, he started to design houses and industrial buildings, while at the same time painting the city around him under his other surname, Rodrigues. As a member of the artist collective "Porto Independents", he took part in all their art exhibitions until 1946 and became a favourite with the national critics. His oil A Ribeira was purchased by the Contemporary Art Museum of Lisbon (the country capital) in 1944, when he was only 24 years old.

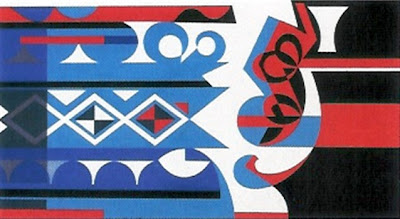

Deux Styles, 1952. Egyptian period (and Baroque period): looking for the geometry imbedded everywhere and in every object.

Art and architecture

In 1946, Nadir Afonso left Porto for Paris with a number of unfinished works from his iris period, and changed his signature with the surname Afonso. There, a Brazilian painter Candido Portinari helped him secure a scholarship from the French Government to study art and painting at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. He resided at the Hôtel des Mines in the Latin Quarter and spent his time regularly at students hangouts. Nadir Afonso recalls this period of his life as the first time that he was in contact with the great world of Art. Because his scholarship lasted only one year, Nadir Afonso worked until 1948 (and again in 1951) with the architect Le Corbusier who, knowing his passion for painting, gave him the mornings off without cutting his salary. He also worked for a while, with the artist Fernand Léger.

Espacillimité, 1954. Espacillimité series: still and moving paintings resulting from the pioneering Kinetic art studies.

Espacillimité, 1954. Espacillimité series: still and moving paintings resulting from the pioneering Kinetic art studies.While working under Le Corbusier in Paris, Nadir Afonso gradually developed his own style of geometric abstractionism. His new fundamentals of aesthetics reoriented his concepts of the origin and essence of art that resulted in his 1948 research thesis controversial to his architectural work, Architecture Is Not an Art. "Architecture is a science, a team elaboration", and therefore a means of expression that cannot satisfy a solitary soul like him. In 1949, Nadir Afonso leaves Paris and for a while immerses himself fully in his paintings. He goes through a period of inspiration in the Portuguese Baroque, followed by an Egyptian period.

Venice, 1956. The beginning of the long-running Cities series, still very connoted with the Espacillimité series.

From December 1951 to 1954, Nadir Afonso crosses the Atlantic to answer an invitation to work with the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer; it was three years of "necessary architecture and obsessive painting." That obsession forces him to return to Paris, looking for artists researching Kinetic art. He joins the group of the Denise René Gallery, connecting with French-Hungarianpainter Victor Vasarely (father of the Op-art), Danish painter Richard Mortensen, French painter Auguste Herbin, and French architect André Bloc, culminating in 1958 in the public showing, at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, of his animated painting Espacillimité (now on display at the Chiado Museum in Lisbon). His first book, La Sensibilité Plastique, is published the same year with the support of art critic Michel Gaüzes, patron Madame Vaugel and Victor Vasarely. In 1959, his first anthology exhibition takes place at the Maison des Beaux-Arts in Paris, while initial exhibitions of his new style in his native country fail initially to raise as much interest as in the early expressionist years.

Occident, 1966. Cities series: the geometric alphabet devised by Nadir Afonso expands beyond Espacillimité.

Full-time painter

Paris is the world center of the arts but the fierce competition between artists proves too much for Nadir Afonso. In 1965, conscious of his social inadaptation, he moves back to his hometown of Chaves and little by little takes refuge in isolation and accentuates the orientation of his life towards the creation of his art. He terminates the architecture practice and pursues his aesthetics studies based on geometry, which he considers the essence of art. Once in a while, he leaves his hideout to return to Paris and meet with friends author Roger Garaudy, painter Victor Vasarely, and critic Michel Gaüzes. By indication of Garaudy, he travels to Toulouse to meet aestheticist Pierre Bru, with whom he reviews the syntactic form of his studies, before publishing Les Mécanismes de la Création Artistique (The Mechanisms of Artistic Creation), the book where he introduces his original theory of art as an exact science.

Port of Copenhagen, 1975. Painting city by city, Nadir Afonso's style will get more abstract in years ahead.

In 1974, he makes a solo exhibition at the Selected Artists Galleries, in New York. U.S. critics acclaim him as "one of the first proponents of geometric abstraction in Portugal [and] one of the new generation European artists."

Living in reclusion, Nadir Afonso defined himself in 2006 as "Portuguese and a son of the inner country. I learned from tradition to be humble, to praise the masters, and to live these eighty-six years with the simplicity that my lowly status has always guaranteed me. To do a balance of my existence and of my work now is absurd." He has spent the last three decades painting, exhibiting, and writing with regular and growing comfort. He is twice married, with five children, born between 1948 and 1989.

Nadir Afonso exhibits regularly in Lisbon, Porto, Paris, New York, and all over the world, and as of 2007 is still active at work. He is represented in museums in Lisbon and Porto (Portugal), Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo (Brazil), Budapest (Hungary), Paris (Pompidou Center), Wurzburg and Berlim (Germany), among others. He has formed a foundation bearing his name, to which he donated his personal artwork collection, and has engaged Pritzker Prize-winner architect Alvaro Siza to design its headquarters in his hometown of Chaves.

Dresden, 1985. The geometric alphabet is still evolving.

International recognition

The recognition of Nadir Afonso's talent came early in his career, both in his home country and internationally. Aged 24, an oil of his, A Ribeira, had already been purchased by the Contemporary Art Museum of Lisbon and the Portuguese government invited him twice to represent Portugal at the São Paulo Art Biennial. By the age of 50, he was well known and regularly exhibited in New York and Paris.

However, his reclusive personality and the memory of his first attempt in 1946 to show his paintings to an art gallery in Paris, which was snubbed and left him humiliated, have since meant that he shies from publicity and no exhibition has ever been promoted by himself. Victor Vasarely, the father of op art, had already noticed it in 1968:

"This artist I have known for over 20 years is undoubtedly the most important Portuguese contemporary painter and his work is unjustly little known across the world."

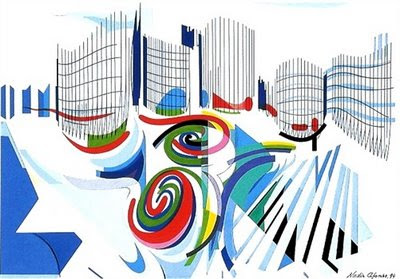

Moscow, 1995. A colorful period in the Cities series, even though Nadir Afonso declares that color is secondary and an afterthought.

Personal aesthetics theory

Art is usually conceived as subjective, but for Nadir Afonso it is purely objective and ruled by laws. "Art is a show of exactitude", "a game of laws in spaces but not of significations in objects". From these axioms, his own personal theory of geometry-based "rational aestetics within an intuitive art" evolved, which he published in book form, alongside his philosophical thoughts on the Universe and its laws. These works are the key to understand the artist and his art, and are summarized by himself in a few words:

"Searching for the absolute, for an art language in which shapes possess a mathematical rigorousness, where nothing needs to be added nor removed. The feeling of total exactitude."

Because of his rationalism, Nadir Afonso confronted Kandinsky, the father of abstract art, and criticized him for subduing geometry to the human spirit instead of making it the essence of art. This "geometry of art" is not however the "geometry of geometrists", as it is not about symbols nor anything in particular; rather, it is the spatial law itself, with the four qualities of perfection, harmony, evocation, and originality.

His work is methodical, because "an artwork is not an act of 'imagination' (...) but of observation, perception, form manipulation." "I start with shapes, still arbitrary. I put ten shapes on the frame; I look at it and suddenly a sort of spark ignites. Then the form appears. Color is secondary, used to accentuate the intensity of the form." Nadir Afonso does not renege on his early expressionist and surrealist works: "An individual initially does not see the true nature of things, he starts by representing the real, because he is convinced therein lies the essence of the artwork. I thought that too. But, as I kept working, the underlying laws of art, which are the laws of geometry, slowly revealed themselves in front of my eyes. There was no effort on my part, it was just the daily work what led me to that result, guided by intuition." The illustrations of this article are a chronological representation of the evolution of Nadir Afonso's style and thought towards the original geometric alphabet with which he creates his artworks, as explained in his books and seen most prominently in his Cities series.

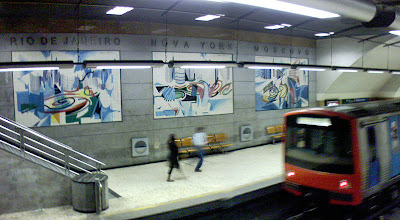

Tile panels on the Lisbon Metro (1998)

Aesthetic Feeling

Nadir Afonso

A) We can feel emotion before an object:

1) Because it reminds us of another object (evocation).

For example: we feel emotion before the tree trunk that reminds us of somebody crucified; before the cloud that suggests an eagle, the garden that appeals to our childhood, the portrait that evokes a loved one;

2) Because the intended function of the object satisfies a need in us or responds to our notion of need (perfection). For example: we feel emotion before the utensil, the glass, the chair, the table, the machine, the functional, practical, light, portable, comfortable vehicle;

3) Because the object presents to us special features (originality). For example: we feel emotion before the black flower, the elegant giraffe, the polar landscape;

B) We can feel emotion before a law:

Because the space itself contains metric laws pertaining to geometric form (harmony). For example: we feel emotion before the lunar circle; before the hexagon of the quartz crystal; before the skyline over the sea.

Paris (years 70)

C) “The creator tries to convey emotion to us”... and it is here that the first aesthetic conflict is born! How can man convey emotion (which comes to him sometimes from a pure feeling of love) when he paints, for example, the portrait of a “loved one”? This emotion is intransmissible! If the artist considers that his picture of the “loved one” is a work of art (because it arouses his emotion), so can the critic consider that it is not (because it does not arouse his emotion) … The same work cannot be declared “artistic” by some and “inartistic” by others!

But there’s more. When the art critic is a “renowned authority on aesthetics” he classifies, for example, the picture of the “tree trunk” under works of art (because it suggests to him, as to the artist and the like, a crucified being) and does not classify the picture “loved one” (because it does not suggest any loved one to him). And if we are careful enough to look into the illusion under which both the art critic and the artist fell, we will see that the same mistake extends to all significations inherent in all objects.

Conclusion of the aesthetic conclusion: it is not in the representation of objects that the characteristics of a work of art lie. Meaning evolves through the environment, the time, the race, the people, according to function, need, belief, culture, affection… and everything that depends on them is an incidental, transitory, individual emotion. Only the laws of space, independent from evolution, contain accuracy, and only they can reveal eternity and universality to us – the absolute to which every true work of art aspires.

Of course, to counter this statement, traditional aesthetics have an argument they consider an inevitable “check mate”: “not all works of art represent geometries – “lunar circles” or “crystal hexagons” and many of the works that represent them cannot help being, despite that, mediocre products”! The answer is right in terms of reasoning and wrong in terms of perception: the laws of space have their most evident expression in the simple forms of Nature: the circle, the square, the equilateral triangle, the hexagon... and in the act of making the work of art this data and its intermediate components becomes more complex according to structures that obey a correlative law: integration and disintegration which we call morphometry. It is these structural rules that weave this factive feeling of perennially and accuracy as if represented things were revealed to us full of “mysterious meanings”. Such a structuring norm is, however, irreducible from intuitive mathematics to constituted sciences and only accessible to the faculties of perception.

Only thus is it understandable that elementary forms – the circle, the hexagon, etc. – do not make in themselves a composite set, as it is understandable that a composite set does not present to scientific reason these primordial geometric elements. Hence, in the same order and sequence, it is understandable that, in the aesthetic view of those who do not grasp these principles, the illusion is formed that the sense of artistic creation emanates from a “revelation” of meaning inherent in objects.

My major concern has been to mark the existence and set out the rules of integration and disintegration of spaces: unsuspected morphometric laws of traditional aesthetics and keystone of my whole work. In particular, my work Le Sens de l’Art seeks essentially, from the first to the last line of text, the natural norms of this geometrisation.

Rio de Janeiro (years 90)

Aesthetes do not agree with me because, if it were as I say, “art would have no mystery”.

Nadir Afonso

Seville, 2007. At age 86, first oversized painting (176x235 cm), using his full geometric alphabet.

Artworks

Nadir Afonso has produced mainly paintings and serigraphs. His current preferred materials are acrylic paint on canvas (bigger works), and gouache on paper (smaller works, often studies for bigger works). His best-known and most distinctive work is the Cities series, each painting usually representing a city from anywhere in the world.